The Great Reform Act of 1832 was passed at the climax of a two year period of high political tension (Evans, 1994, p.1) to soothe the boiling blood of working class people in Britain. MPs were afraid of the tyranny of the French Revolution and wanted to appease the working class in order to prevent a full blown revolution in Britain. It was an attempt to bandage a gaping wound in order to protect their property, class structure and way of life.

The Reform Act was flawed but a step in the right direction, it abolished the rotten boroughs, which were ridiculous in the first place. Parliamentary seats fell into two broad categories: county and borough. Each English County regardless of its size or population had two members of parliament. This highly underrepresented Scotland, Ireland and Wales and densely populated areas of Britain. It was highly unfair as Scottish members of Parliament needed to have property valued at over £100 whereas in England their property needed only amount to £2 (Evans, 1994, p.1).

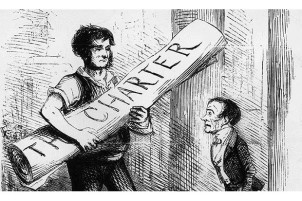

The air was static with the possibility of revolution. The atrocity of the Peterloo Massacre in 1819 still cast a black cloud over the working class who were fed up and angry at the political system. Groups such as the The London Corresponding Society and the Luddites were demanding representation in government. How was it fair that their livelihoods were directed by the aristocracy who had never worked a hard day in their life? The under-representation of Britain’s leading commercial and industrial centres became more difficult to justify with every year that passed (Evans, 1994, p.17).

The distribution of seats act was a distraction from universal suffrage. It still kept the power in the hands of the aristocracy but it distracted the working class from a bloody revolution for the time being. It goes to show that Britain was about reform from above rather than allowing things to get out of control. I believe that the upper class implemented the Reform Act in order to appease the middle class in order to avoid them siding with the working class.

Economic distress causes civil unrest. When people are hungry and don’t feel that they are being fairly treated while people are living in affluent luxury they begin to get agitated and push for reform or begin to riot. William Cobbett famously defied anyone “to agitate a fellow on a full stomach”. He said to the public that their main problem was misgovernment. A landowners parliament was wasting people’s hard earned taxes on lavish expenditure, patronage and corruption.

The upper middle class gained the most from this act. The upper and middle classes were afraid of the lower classes. They gave the middle class the vote in order to buy their loyalty to avoid them siding with the lower classes and forming a revolution.